Program

Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643 – 1704)

Prelude from Te Deum

Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562 – 1621)

Variations on “Onder een Linde Groen”

Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583 – 1643)

Recercar dopo il Credo from “Fiori Musicali”

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 – 1750)

Prelude and Fugue in C Major, BWV 545

INTERMISSION

Percy Whitlock (1903 – 1946)

Folk Tune

William Albright (1944 – 1998)

Sweet Sixteenths: A Concert Rag for Organ

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 – 1750)

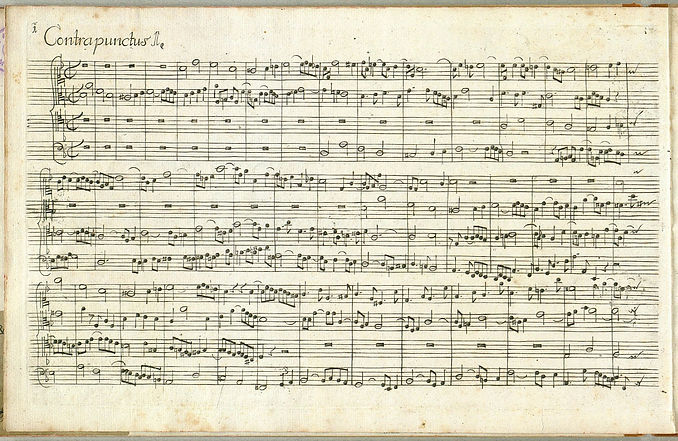

Contrapunctus I from “Art of Fugue,” BWV 1080

Stéphane Delplace (b. 1953)

Bach Panther

[ Pink Panther theme by Henry Mancini (1924 – 1994) ]

Charles-Marie Widor (1844 – 1937)

Toccata from Symphony No. 5, in F minor, Opus 42, No. 1

Please silence all electronic devices.

Program Notes

Tonight’s program is a brief tour of European organ music styles and history with a few detours and links to the New World. We will hear music from England, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands and The United States. Not all of this music was originally composed for the organ, but these pieces provide an excellent opportunity to hear the many sound colors offered by the two organs in Westerkerk.

Anyone who has watched television in Europe will immediately recognize Charpentier’s “Prelude from Te Deum” which is used by the European Broadcasting Union as its signature tune. Charpentier composed his grand polyphonic motet Te Deum in D major probably between 1688 and 1698, during his stay at the Jesuit Church of Saint-Louis in Paris, where he held the position of musical director. The work is written for the group of soloists, choir, and instrumental accompaniment. In this version for solo trumpet and organ, the solo is played on one organ manual by one organist while the other organist performs on two manuals and pedals.

Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck was called the “Father of German Organists.” Numerous German city-states and churches sent their organists to Amsterdam to study with him. Sweelinck composed fine examples of organ works in numerous styles, including highly sophisticated imitative works, brilliant toccatas, echo fantasies, and chorale-based pieces. Today’s work is one of numerous delightful variation sets on secular tunes, perfect for showing off the stops of both organs in Westerkerk.

Fiori Musicali was first published in Venice in 1635, when Frescobaldi was working as organist of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, under the patronage of Pope Urban VIII and his nephew Cardinal Francesco Barberini. It may have been conceived as music for St Mark’s Basilica or a similarly important church. The collection was printed by Giacomo Vincenti (a celebrated publisher who had previously published reprints of Frescobaldi’s capriccios), and dedicated to Cardinal Antonio Barberini, Francesco’s younger brother. The full title of Frescobaldi’s work is Fiori musicali di diverse compositioni, toccate, kyrie, canzoni, capricci, e recercari, in partitura a qvattro vitili per sonatori.

Johann Sebastian Bach composed several C Major prelude-and-fugue sets. BWV 545 went through a particularly rich development process. To the original prelude, Bach added several opening and concluding toccata measures. In another source the piece is found in B-flat Major. He also in one source added the slow largo movement from his fifth trio sonata (BWV 529). The fugue itself is a concise alla breve movement of great power.

Percy William Whitlock studied at London’s Royal College of Music with Charles Villiers Stanford and Ralph Vaughan Williams. From 1921–1930, Whitlock was assistant organist at Rochester Cathedral in Kent. He served as Director of Music at St Stephen’s Church, Bournemouth for the next five years, combining this from 1932 with the role of that town’s borough organist, in which capacity he regularly played at the local Pavilion Theatre. After 1935 he worked for the Pavilion Theatre full-time. His “Folk Tune” is from the collection “Five Short Pieces” published in 1930.

William Albright was born in Gary, Indiana, and began learning the piano at the age of five, and attended the Juilliard Preparatory Department, the Eastman School of Music and the University of Michigan. During the 1968–69 academic year he received a Fulbright scholarship to study with Olivier Messiaen in Paris. Upon his graduation in 1970 he was appointed to the faculty of the University of Michigan, where he taught until his death in 1998. His music combines elements of tonal and non-tonal classical music with American popular music and non-Western music, in what has been described as “polystylistic” or “quaquaversal” music which makes the definition of an overall style difficult. In particular, he was an enthusiast for ragtime and made notable recordings of the piano rags of Scott Joplin and others. He also recorded an album of his own Ragtime compositions.

One of the great works of musical art ever composed is Bach’s Art of Fugue, compiled in the last decade of his life, preserved in two primary sources emanating from Bach himself—an early manuscript version and a posthumous print. Much controversy and confusion has accompanied the work over the centuries, mainly due to two issues: the printed form of the work is in “open score” (individual staves for each voice part), meaning the performing forces are not clearly indicated. Also, a massive Fuga a 3 soggietti (fugue with three subjects, none of which is the main theme of the set) was left incomplete. Today’s movement, the first in the collection, while displaying Bach’s characteristic didactic intensity, is also extremely beautiful and includes two unexpected, dramatic silences before the end. A final pedal point begs the question: Did Bach perhaps see the organ as the ideal instrument for the collection?

Enrico Nicola “Henry” Mancini (1924–1994) was born in the “Little Italy” neighborhood of Cleveland, Ohio and was raised in the steel town of West Aliquippa, Pennsylvania. His parents immigrated from the Abruzzo region of Italy. Mancini’s father, Quinto was a steelworker, who made his only child begin piccolo lessons at the age of eight. When Mancini was 12 years old, he began piano lessons. Quinto and Henry played flute together in the Aliquippa Italian immigrant band, Sons of Italy. Mancini briefly attended the renowned Juilliard School of Music in New York before being drafted into the Army. He is best remembered for his film and television scores and many “easy listening” hits such as Days of Wine and Roses and Moon River. He won four Academy Awards, a Golden Globe, and twenty Grammy Awards, plus a posthumous Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1995. The Pink Panther theme is given a Bach-style fugal treatment here by French composer Stéphane Delplace and is taken from his first of two collections entitled “Préludes & Fugues dans les Trente Tonalités.”

in the mid 19th century, technological advances allowed new features to be added to the organ, increasing its potential for expression. The work of the French organ builder Aristide Cavaillé-Coll (1811–1899) in particular represented a great leap in organ building. Cavaillé-Coll refined the English Swell box by devising a spring-loaded (later balanced) pedal with which the organist could operate the swell shutters. He invented an ingenious pneumatic combination action system for his five-manual organ at Saint-Sulpice in Paris. He adjusted pipemaking and voicing techniques, thus creating a whole family of stops imitating orchestral instruments such as the bassoon, the oboe, and most famously the Harmonic Flute. He introduced divided windchests which were controlled by ventils, allowing for the use of higher wind pressures. For a mechanical tracker action to operate under these higher wind pressures, pneumatic assistance provided by the Barker Lever was required, which Cavaillé-Coll included in his larger instruments. This pneumatic assist made it possible to couple all the manuals together and play on the full organ without expending a great deal of effort. All these innovations allowed the organist to execute a seamless crescendo from pianissimo all the way to fortissimo: something that had never before been possible by the organ. Composers were now able to write music for the organ which mirrored that played by the symphony orchestra. For this reason, both the organs and the literature of this time period are considered symphonic.

Charles-Marie Widor (1844–1937), Cesar Franck (1822–1890) Louis Vierne (1870–1937), and Felix-Alexandre Guilmant (1837–1911) were important organist-composers who were inspired by the sounds made possible through Cavaillé-Coll’s advances in organ building. They wrote extensively for the organ, and their works have endured. A particularly important form of organ composition in the Romantic era was the Organ Symphony, first seen in Cesar Franck’s Grande Pièce Symphonique and refined in the six symphonies of Louis Vierne ten of Widor.

Widor’s famous toccata concludes his masterful Fifth Organ Symphony. Perpetual motion in the manuals on full organ, with brilliant arpeggios and sharply repeated chords, is answered by a pedal melody in long notes. After the opening section, the volume is reduced to just a single division (the closed Swell division on a French symphonic organ). A wonderful build up—accomplished here in Westerkerk by adding stops and coupling manuals—leads to a recapitulation of the opening idea, this time with the melody in octaves in the pedal. A coda section brings this brilliant piece to a close.

—Rodney Gehrke and Ole Jacobsen with lots of help from Wikipedia